Thursday, May 18, 2006

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

What Would it Mean to "Win" the "War on Terror"?

This is exactly right.

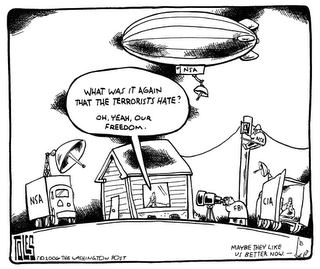

I've had my share of heated debates with conservatives who claim we are winning the war on terror because we haven't been attacked since 9/11. But only those with a myopic view of the conflict can make such a claim. Limiting the definition of success solely to the physical safety of Americans fails to take into account that the goal of al Qaeda is not merely to cause death, but to cause a destruction of the very thing that defines us as Americans: our freedom.

As the President said the day the towers fell, "our way of life, our very freedom" was attacked. And how have we responded in the past five years? Not by preserving our way of life, not by zealously gaurding our freedom, but by surrendering.

Read the whole thing.

In a previous post I said I wasn't afraid of terrorism. I was in Washington, D.C. on the morning of 9-11 and since I work for the federal government, which presumably remains a terrorist target generally, and since I commute to work in D.C. via the metro rail system--as likely a terrorist target as any in the area, I think I have as much right as anyone to speak for those of us most likely to be affected by future terrorist actions. And I ain't afraid. And I ain't moved by conservative bullying to surrender my first and fourth amendment rights to pacify their own fears or satisfy their authoritarian ambitions.

John Kerry was criticized by fear-mongering right-wingers for saying during one of the debates that he hoped or looked forward to the day when the threat of terrorism would be merely an inconvenience. But Kerry was right to say that, however it may have offended the 101st Fighting Keyboarders.

Democrats basically let Republicans use fear as a baseball bat during the last two election cycles. At the same time, there have been some leading or at least high profile Democrats (Peter Beinert, the DLC) who have stressed the need for Democrats to convince the public they are "serious about national security" and will protect them, and thereby played into Republican hands. That tactic has been a political as well as substantive failure and abdication of the party's responsibility to uphold and protect the Constitution. Here's hoping Democrats have learned something and have the courage to push back on the conservative fear meme.

I've had my share of heated debates with conservatives who claim we are winning the war on terror because we haven't been attacked since 9/11. But only those with a myopic view of the conflict can make such a claim. Limiting the definition of success solely to the physical safety of Americans fails to take into account that the goal of al Qaeda is not merely to cause death, but to cause a destruction of the very thing that defines us as Americans: our freedom.

As the President said the day the towers fell, "our way of life, our very freedom" was attacked. And how have we responded in the past five years? Not by preserving our way of life, not by zealously gaurding our freedom, but by surrendering.

Read the whole thing.

In a previous post I said I wasn't afraid of terrorism. I was in Washington, D.C. on the morning of 9-11 and since I work for the federal government, which presumably remains a terrorist target generally, and since I commute to work in D.C. via the metro rail system--as likely a terrorist target as any in the area, I think I have as much right as anyone to speak for those of us most likely to be affected by future terrorist actions. And I ain't afraid. And I ain't moved by conservative bullying to surrender my first and fourth amendment rights to pacify their own fears or satisfy their authoritarian ambitions.

John Kerry was criticized by fear-mongering right-wingers for saying during one of the debates that he hoped or looked forward to the day when the threat of terrorism would be merely an inconvenience. But Kerry was right to say that, however it may have offended the 101st Fighting Keyboarders.

Democrats basically let Republicans use fear as a baseball bat during the last two election cycles. At the same time, there have been some leading or at least high profile Democrats (Peter Beinert, the DLC) who have stressed the need for Democrats to convince the public they are "serious about national security" and will protect them, and thereby played into Republican hands. That tactic has been a political as well as substantive failure and abdication of the party's responsibility to uphold and protect the Constitution. Here's hoping Democrats have learned something and have the courage to push back on the conservative fear meme.

What about the Canadian Border?

Although I can't say I'm terribly concerned about the threat of terrorism generally or the threat of would-be terrorists crossing the Mexican border in particular, I have to admit that the need to tighten our borders to guard against the potential from terrorist infiltration at least has some logical merit.

Which is why I'm a little surprised that that angle hasn't been a real common one in the array of anti-immigration complaints I've been hearing, watching, or reading about.

Most of the anti-immigrant apologetics seem either spurriously convenient (illegal immigrants drive down wages) or blatantly racist (illegal immigration from Mexico is why phone services have "if you speak English, press 1" options).

Moreover, if stopping terrorist infiltration was the over-riding concern, as I would think it would be in a post-911 world, where is the call for walling off our Canadian border? Surely terrorist infiltration, if it is to come, is just as likely, if not more so, to come over the Canadian border as over the Mexican one.

No, despite all the frantic demands on the part of the right that we abandon any and all civil liberties to ensure we aren't attacked by terrorists again, the terrorist threat potentially posed by immigration seems almost off the radar. This leads me to think that neither the rabidly anti-civil liberties right nor the rabidly anti-immigration right are sincere (imagine that). Of course, even were terrorism the main fear element of the anti-immigration movement, it wouldn't mean it wasn't based in part or in whole on racist fears and demogoguery.

But the relative absence of terrorism from the anti-immigration debate is suprising nonetheless.

Which is why I'm a little surprised that that angle hasn't been a real common one in the array of anti-immigration complaints I've been hearing, watching, or reading about.

Most of the anti-immigrant apologetics seem either spurriously convenient (illegal immigrants drive down wages) or blatantly racist (illegal immigration from Mexico is why phone services have "if you speak English, press 1" options).

Moreover, if stopping terrorist infiltration was the over-riding concern, as I would think it would be in a post-911 world, where is the call for walling off our Canadian border? Surely terrorist infiltration, if it is to come, is just as likely, if not more so, to come over the Canadian border as over the Mexican one.

No, despite all the frantic demands on the part of the right that we abandon any and all civil liberties to ensure we aren't attacked by terrorists again, the terrorist threat potentially posed by immigration seems almost off the radar. This leads me to think that neither the rabidly anti-civil liberties right nor the rabidly anti-immigration right are sincere (imagine that). Of course, even were terrorism the main fear element of the anti-immigration movement, it wouldn't mean it wasn't based in part or in whole on racist fears and demogoguery.

But the relative absence of terrorism from the anti-immigration debate is suprising nonetheless.

Immigration--A Tipping Point?

I don't know if we've reached, or are reaching a Tipping Point where the Republican majority begins to disintegrate, but I think there are a number of reasons to wonder where the conservative movement goes from here, especially if the conservative chatter after last night's prez address is at all reflective of the movement's strains.

As Glenn Greenwald suggests, the Republican Party breakdown on immigration, at this particular time, probably owes a lot to the fact that the war in Iraq has failed to live up to its billing; it's producing neither clear-cut military or moral victories.

But as Barbara at Mahablog discusses, there's certainly more going on, above as well as beneath the surface, here than immigration politics and the war in Iraq. The last four decades have represented what political scientists refer to as a secular realignment; a realignment in party control that develops over a period of time, as opposed to the type of party realignments that stems from a crisis event (i.e. the Great Depression). That gradual-ness has allowed the party elite to draw ever widening groups of the electorate into its fold, largely based on symbolic and rhetorical gestures (the flag, religious values, etc) without signficantly altering the basic structure of American society and government and without therefore turning off essential components of the political middle. The downside for the Republican Party is that its more baser elements are tired of the slow process of change and now want more visible and substantive results. The party's further downside is that to implement the changes demanded by its baser elements would be infeasible.

The appointment of two conservative justices to the Surpreme Court, and the passage in South Dakota of an abortion-criminalization law highlight the risk involved in moving the party further to the right on social issues. It was one thing to call abortion murder when conservatives weren't running all three branches of government. It's another thing alltogether to implement the logical extensions of the abortion-is-murder argument and criminalize abortion providers and abortion consumers.

Taxes represent another problematic front. Cutting government to the bone was a lot easier spoken of in theory, from outside the halls of power, than it was once the party was in charge of government. Even though conservatives were more than willing to let most dimensions of federal capabilities and authority whither on the vine (like FEMA), today's conservative movement actually has little to do with the frequent calls for "smaller government" that it's rhetoricians have been broadcasting at least since the Reagan era. Conservatives very much want big government to do things--like "enforce our borders" and eliminate the opposition (us liberals). Those types of things tend to require government employees and structure of some kind, which all in turn, require money. Tax money. The marginal utility to be derived from the "tax cuts today, tomorrow, and forever" part of the Republican Party platform is all but used up.

Finally, the "war on terror" rhetoric is also wearing thin. Wars are exciting for a certain class of the conservative movement. But unfortunately for this class, they are finding out that war is a pretty limited instrument, especially when it's discovered that it involves material and physical sacrifice to implement. And this most conservatives, comfortable in their homes with their keyboards, are unwilling to follow through on.

This reluctance to put its money where its mouth is, is probably the decisive factor preventing (at least for now) the full flowering of a fascist party in the U.S. Conservatives talk tough, they may make death threats to celebrities or schoolchildren, they may call for eliminating liberals from their audiences, from the nation's campuses, and from society, but in the final analysis, the conservative movement lacks the Will to implement its dreams. It is cowardly.

Put simply, the conservative movement is at, or at least very near, a breaking point between its rhetorical and symbolic goals on the one hand, and the policy choices needed to implement its rhetoric on the other.

As Glenn Greenwald suggests, the Republican Party breakdown on immigration, at this particular time, probably owes a lot to the fact that the war in Iraq has failed to live up to its billing; it's producing neither clear-cut military or moral victories.

But as Barbara at Mahablog discusses, there's certainly more going on, above as well as beneath the surface, here than immigration politics and the war in Iraq. The last four decades have represented what political scientists refer to as a secular realignment; a realignment in party control that develops over a period of time, as opposed to the type of party realignments that stems from a crisis event (i.e. the Great Depression). That gradual-ness has allowed the party elite to draw ever widening groups of the electorate into its fold, largely based on symbolic and rhetorical gestures (the flag, religious values, etc) without signficantly altering the basic structure of American society and government and without therefore turning off essential components of the political middle. The downside for the Republican Party is that its more baser elements are tired of the slow process of change and now want more visible and substantive results. The party's further downside is that to implement the changes demanded by its baser elements would be infeasible.

The appointment of two conservative justices to the Surpreme Court, and the passage in South Dakota of an abortion-criminalization law highlight the risk involved in moving the party further to the right on social issues. It was one thing to call abortion murder when conservatives weren't running all three branches of government. It's another thing alltogether to implement the logical extensions of the abortion-is-murder argument and criminalize abortion providers and abortion consumers.

Taxes represent another problematic front. Cutting government to the bone was a lot easier spoken of in theory, from outside the halls of power, than it was once the party was in charge of government. Even though conservatives were more than willing to let most dimensions of federal capabilities and authority whither on the vine (like FEMA), today's conservative movement actually has little to do with the frequent calls for "smaller government" that it's rhetoricians have been broadcasting at least since the Reagan era. Conservatives very much want big government to do things--like "enforce our borders" and eliminate the opposition (us liberals). Those types of things tend to require government employees and structure of some kind, which all in turn, require money. Tax money. The marginal utility to be derived from the "tax cuts today, tomorrow, and forever" part of the Republican Party platform is all but used up.

Finally, the "war on terror" rhetoric is also wearing thin. Wars are exciting for a certain class of the conservative movement. But unfortunately for this class, they are finding out that war is a pretty limited instrument, especially when it's discovered that it involves material and physical sacrifice to implement. And this most conservatives, comfortable in their homes with their keyboards, are unwilling to follow through on.

This reluctance to put its money where its mouth is, is probably the decisive factor preventing (at least for now) the full flowering of a fascist party in the U.S. Conservatives talk tough, they may make death threats to celebrities or schoolchildren, they may call for eliminating liberals from their audiences, from the nation's campuses, and from society, but in the final analysis, the conservative movement lacks the Will to implement its dreams. It is cowardly.

Put simply, the conservative movement is at, or at least very near, a breaking point between its rhetorical and symbolic goals on the one hand, and the policy choices needed to implement its rhetoric on the other.

Defending Joe Klein*

So Joe's gone and done it again--put his foot in the mouth with some derogatory comments about members of the Democratic Party. And those angry, leftish bloggers are giving him hell.

But I'm afraid Joe needs some sympathy here. Yes, yes, it's true that Charley Rangel and John Conyers are technically war vets, but that doesn't change the fact that their long congressional careers are an embarassment. An embarassment How and to Who you ask? Why, to Joe Klein of course.

Try to put yourself in Joe's shoes. He's got a kool gig at Time, writin' a weekly column, hanging out with the other kool kidz; and he does all those cable TV "news" programs, where he's a special kinda pundit, the "liberal" kind. And as much fun and rewarding the comradery and cash are from these posts, the truth is it continually puts him in the difficult position of having to try to defend liberalism and liberals to all his conservative friends. And it would sure be a lot easier to do that if the liberal party's leadership didn't contain black folks, and the worse kind of black folks--the kind that aim to raise a fuss.

And what's all this talk about hearings and impeachments if Democrats win Congress? That's not how we unite a divided nation or reassure the real, regular Americans in fly-over country.

Joe notices his friends raise their eyebrows whenever uppitidy Democrats show up with inflammatory comments in the press, and it embarasses him. Joe wishes these Dems would be quiet.

And besides, don't Democrats realize that if they allow black Democrats a prominent place in committees and in the media, that the nice Republicans will be forced to make race and Democratic anger issues in the 2006 campaign? And don't Democrats realize that the sight of angry, black Democrats in Congress trying to lead investigations into a popular administration will cause a backlash among centrist voters? Joe is really trying to do "his" party a favor.

So all you angry, lefty-liberal bloggers, you lay off of Joe Klein.

*This post is intended as Satire.

But I'm afraid Joe needs some sympathy here. Yes, yes, it's true that Charley Rangel and John Conyers are technically war vets, but that doesn't change the fact that their long congressional careers are an embarassment. An embarassment How and to Who you ask? Why, to Joe Klein of course.

Try to put yourself in Joe's shoes. He's got a kool gig at Time, writin' a weekly column, hanging out with the other kool kidz; and he does all those cable TV "news" programs, where he's a special kinda pundit, the "liberal" kind. And as much fun and rewarding the comradery and cash are from these posts, the truth is it continually puts him in the difficult position of having to try to defend liberalism and liberals to all his conservative friends. And it would sure be a lot easier to do that if the liberal party's leadership didn't contain black folks, and the worse kind of black folks--the kind that aim to raise a fuss.

And what's all this talk about hearings and impeachments if Democrats win Congress? That's not how we unite a divided nation or reassure the real, regular Americans in fly-over country.

Joe notices his friends raise their eyebrows whenever uppitidy Democrats show up with inflammatory comments in the press, and it embarasses him. Joe wishes these Dems would be quiet.

And besides, don't Democrats realize that if they allow black Democrats a prominent place in committees and in the media, that the nice Republicans will be forced to make race and Democratic anger issues in the 2006 campaign? And don't Democrats realize that the sight of angry, black Democrats in Congress trying to lead investigations into a popular administration will cause a backlash among centrist voters? Joe is really trying to do "his" party a favor.

So all you angry, lefty-liberal bloggers, you lay off of Joe Klein.

*This post is intended as Satire.

Sunday, May 14, 2006

American Theocracy's Hostile Takeover, Part 1

Picked up the Philips and Sirota books last week and have read a few chapters from each. I think both books represent opposite sides of the same coin. Philips' is generally a macro perspective of the effects of corporate conglomeration and political influence on aggregate U.S. finances and the U.S.'s role in the international system, while Sirota's is more of a micro analysis, concerned more about the distributional impacts of recent corporate induced policies flowing out of Washington on the American middle class. And both books in turn sound a great deal like Thomas Franks' What's the Matter with Kansas? that came out last year, synthesizing the conservative movement's melding of economic corporatism and religious fundamentalism.

Sirota's book covers a wider range of specific policies, from taxes to debt and pensions. Although each chapter can be read alone, it's clear they are linked, all representing how Big Business has acted to reduce the participation and influence of workers and consumers by funding political campaigns, formulating policy options, and manipulating public opinion to further its goals.

Sirota's book is certainly the more infuriating of the two. Reading the chapters on debt and legal rights, for example, is enough to make you want to shoot somebody in the face (by accident of course, during a hunting trip). The tone and structure of the book is in some ways similar to the style of conservative reactionary pamphlets on "moral relativism", moral values, religion in the public square, etc, that the Mellon's and Scaife's have financed over the past couple of decades from the right, meant to shock and inflame, but on closer examination, lacking the sort of context, nuance and balance necessary for a well-informed view on the issues. For example, in the pensions chapter, Sirota refers to the (relatively recent) corporate practice of converting traditional defined benefit (db) pension plans for employees into "cash-balance" plans, leaving the recipient with a lump sum distribution presumably lower than what an annuitized db payout would provide. But Sirota doesn't indicate how prevalent this is or what it's magnitude is in the market-place.

Sirota also provides anecdotal evidence of cases in which corporations (like United Airlines) have apparently sued the employees or retirees in order to recoup or limit their pension obligations. But Sirota doesn't mention the protection offered employees by way of the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation, which insures private, db style pension plans. Nor does Sirota refer to the shift in private pension plan coverage from db to defined contribution (dc), which while it offers some employees the potential for higher investment returns, also involves a shift in risk from the employer (i.e. social or collective risk) to the worker and retiree (i.e. individual risk). This shift in risk is an important feature of Sirota's overall narrative (and an important political dynamic I think) and I'm a bit surprised he doesn't make this connection.

Likewise, while last year's bankrupcy "reform" bill was truly excretable, a payback to credit card companies that generously fund congressional campaigns and a shaft to vulnerable families, and while the loan shark level of interest rates companies can charge is inherently immoral and predatory, Sirota's, and the Democratic Party's opportunity for generating the appropriate public outrage over them will be difficult as long as the middle class homes in neighborhoods like mine continue to showcase one or two SUV's. If people are doing well, if unemployment is low, if the economy is "growing", I suspect that Democratic efforts to drive up middle class economic angst through a populist sort of appeal may fall short. It's worth trying, and the corruptness of the current regime and processes need to be pointed out, but I'm not optimistic.

In short, while Sirota is good at dialing up the outrage for us progressive types, as long as the political economy debate is confined to individual anectdotes and issues of redistribution progressives will probably have a hard time making use of them.

More interesting to me in some ways and more important in the long run I believe is the implication many of these policies--and the forces making them operative--have for the U.S.'s overall economic health, financial stability, and standing in the international arena.

Here's where Philips' book comes in. Philips takes many of the strands of Sirota's book and weaves them into a larger narrative of how the U.S. is weakened nationally and internationally through policies favoring financial deregulation, debt expansion, and oil dependence. Philips provides data showing that the U.S. economic sector has changed dramatically in the past 20 to 30 years, from one based on manufacturing to one based on financial services. And contrary to standard conservative economic philosophy which asserts that the U.S. national government shouldn't pick winners or losers, Philips asserts that U.S. policymakers have done just that in encouraging financial deregulation, allowing banking and insurance interests, for example, to both be conducted under the auspices of particular companies. Likewise, the increase in debt by the government and by U.S. households provides an additional troubling harbinger of future economic prospects.

Philips' perspective thus provides a framework for understanding how individual policy choices, like the kind Sirota highlights, shape the nation's overall economic future in the aggregate and how we can understand the apparent disjunction between soaring personal debt and a growing economy. Based on Philips' data and arguments, both individual and national economic prosperity are at a considerable risk given our consumption and financing patterns.

Of course, America's economic hegemony has been pronounced dead, or at least on life support before, only to rebound at least in the short run. But the data and narratives contructed by Sirota and Philips, originating largely from unrelated points on the political-economic map, would seem to indicate that the U.S. economy and political superstructure could be soon facing a point of reckoning. At least we can say we've been warned.

As I finish reading these books I hope to have more to say on these issues, especially Philips' explanation of how religious changes in America have contributed to its economic ones.

For now, if you're wondering what's going on at the political level, given recent developments with the NSA, read this.

Sirota's book covers a wider range of specific policies, from taxes to debt and pensions. Although each chapter can be read alone, it's clear they are linked, all representing how Big Business has acted to reduce the participation and influence of workers and consumers by funding political campaigns, formulating policy options, and manipulating public opinion to further its goals.

Sirota's book is certainly the more infuriating of the two. Reading the chapters on debt and legal rights, for example, is enough to make you want to shoot somebody in the face (by accident of course, during a hunting trip). The tone and structure of the book is in some ways similar to the style of conservative reactionary pamphlets on "moral relativism", moral values, religion in the public square, etc, that the Mellon's and Scaife's have financed over the past couple of decades from the right, meant to shock and inflame, but on closer examination, lacking the sort of context, nuance and balance necessary for a well-informed view on the issues. For example, in the pensions chapter, Sirota refers to the (relatively recent) corporate practice of converting traditional defined benefit (db) pension plans for employees into "cash-balance" plans, leaving the recipient with a lump sum distribution presumably lower than what an annuitized db payout would provide. But Sirota doesn't indicate how prevalent this is or what it's magnitude is in the market-place.

Sirota also provides anecdotal evidence of cases in which corporations (like United Airlines) have apparently sued the employees or retirees in order to recoup or limit their pension obligations. But Sirota doesn't mention the protection offered employees by way of the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation, which insures private, db style pension plans. Nor does Sirota refer to the shift in private pension plan coverage from db to defined contribution (dc), which while it offers some employees the potential for higher investment returns, also involves a shift in risk from the employer (i.e. social or collective risk) to the worker and retiree (i.e. individual risk). This shift in risk is an important feature of Sirota's overall narrative (and an important political dynamic I think) and I'm a bit surprised he doesn't make this connection.

Likewise, while last year's bankrupcy "reform" bill was truly excretable, a payback to credit card companies that generously fund congressional campaigns and a shaft to vulnerable families, and while the loan shark level of interest rates companies can charge is inherently immoral and predatory, Sirota's, and the Democratic Party's opportunity for generating the appropriate public outrage over them will be difficult as long as the middle class homes in neighborhoods like mine continue to showcase one or two SUV's. If people are doing well, if unemployment is low, if the economy is "growing", I suspect that Democratic efforts to drive up middle class economic angst through a populist sort of appeal may fall short. It's worth trying, and the corruptness of the current regime and processes need to be pointed out, but I'm not optimistic.

In short, while Sirota is good at dialing up the outrage for us progressive types, as long as the political economy debate is confined to individual anectdotes and issues of redistribution progressives will probably have a hard time making use of them.

More interesting to me in some ways and more important in the long run I believe is the implication many of these policies--and the forces making them operative--have for the U.S.'s overall economic health, financial stability, and standing in the international arena.

Here's where Philips' book comes in. Philips takes many of the strands of Sirota's book and weaves them into a larger narrative of how the U.S. is weakened nationally and internationally through policies favoring financial deregulation, debt expansion, and oil dependence. Philips provides data showing that the U.S. economic sector has changed dramatically in the past 20 to 30 years, from one based on manufacturing to one based on financial services. And contrary to standard conservative economic philosophy which asserts that the U.S. national government shouldn't pick winners or losers, Philips asserts that U.S. policymakers have done just that in encouraging financial deregulation, allowing banking and insurance interests, for example, to both be conducted under the auspices of particular companies. Likewise, the increase in debt by the government and by U.S. households provides an additional troubling harbinger of future economic prospects.

Philips' perspective thus provides a framework for understanding how individual policy choices, like the kind Sirota highlights, shape the nation's overall economic future in the aggregate and how we can understand the apparent disjunction between soaring personal debt and a growing economy. Based on Philips' data and arguments, both individual and national economic prosperity are at a considerable risk given our consumption and financing patterns.

Of course, America's economic hegemony has been pronounced dead, or at least on life support before, only to rebound at least in the short run. But the data and narratives contructed by Sirota and Philips, originating largely from unrelated points on the political-economic map, would seem to indicate that the U.S. economy and political superstructure could be soon facing a point of reckoning. At least we can say we've been warned.

As I finish reading these books I hope to have more to say on these issues, especially Philips' explanation of how religious changes in America have contributed to its economic ones.

For now, if you're wondering what's going on at the political level, given recent developments with the NSA, read this.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)